“U.S. MARINE CORPS PRE-WAR TRAINING AND THE BATTLE OF BELLEAU WOOD: 1917-1918”

I: Introduction

The fighting in Belleau Wood, France,

in June, 1918 saw the command of the U.S. Marine 6th Machine

Gun Battalion change hands four times in 11 days. Such was the nature of the

vicious fight between the 4th Marine Brigade of the 2nd Infantry

Division (U.S. Army) and the Germans pushing towards Paris. By all accounts,

this first real test of the U.S Marines in the First World War, was a

bloodletting that should have ended in a rout as the experienced and veteran

German machine gunners tore into the inexperienced U.S. Marines. Rather than

collapse, the 4th Marine Brigade withstood the German assaults and not

only held firm, but triumphed. The U.S. Marine Corps 5th and 6th Marine

Regiments in 1918 fought against the veteran and very experienced German

infantry. This study seeks to identify how ad hoc Marine Corps infantry

battalions and the newly formed 4th Marine Brigade was able to not only

stop the German advance, but ultimately prevail, over a much more experienced

enemy in an environment such as the industrialized battlefield of northern

France in World War 1.

1,032 U.S. Marines died in 31 days of constant

fighting in the month of June, 1918. A further 3,615 Marines were wounded in

that same action. June 1918 was the costliest month in the entire history of

the United States Marine Corps. Belleau Wood, an old hunting

preserve, is a small wood surrounded by wheat fields that lays 50

miles from Paris proper. The Battle of Belleau Wood (Bois de Belleau) was the

first serious action of the United States Marine Corps in the First World War.

Two regiments, the 5th and the 6th Marines, engaged the German Army

and saw close quarters fighting, the use of bayonet, artillery, machine guns, mustard gas, and air attacks. Of all the weapons employed by the U.S. Marines, the most

fundamental was employed with incredible accuracy; the rifle.

The First World War, by 1918, had already seen

millions killed and maimed in what proved to be the first industrial sized war.

The United States, under President Woodrow Wilson, had remained a neutral but

sympathetic party to the conflict that consumed so many across Europe.

Unrestricted German submarine warfare across the Atlantic would eventually

compel the United States and Wilson to enter the war in April of 1917. The

declaration of war, by the United States forced a general mobilization and draft

of recruits across the United States. Three months after the declaration of war

by the United States, the U.S. Army established the ‘American Expeditionary

Force’ under General John J. Pershing for service in Europe.

Of the 40+ Infantry Divisions[1] to be established, including active, new,

and National Guard Divisions, the Second Infantry Division was assembled with

one Brigade from the U.S. Army and another Brigade, from the United States

Marine Corps. The Division, quickly assembled from units across the Army and

the Marine Corps, would be rushed into action in northern France. General

Pershing, commander of the American Expeditionary Force (AEF), was not at all

inclined to incorporate the U.S. Marine regiments in his combat

divisions. His initial instinct was to assign the Marines stevedore

and port guard duties. At issue was the unknown entity that the Marines represented

to the U.S. Army. Pershing was busy of course, attempting to orchestrate the

largest mobilization of manpower in U.S. Army history. Pershing cabled the War

Department “stating that “he found the 5th Marine Regiment indigestible and

asked that no more Marines be sent to France.”[2] The

Secretary of War overruled Pershing and would see to it that a Marine Brigade

would participate alongside the U.S. Army in the Great War in Europe.

Official

history of the U.S. Army states that the average soldier received six months of

training prior to seeing action in the trenches across France. Some regiments

and battalions were never committed to the savage fighting in the closing

months of 1918. The average battalion, however, once deployed to France, would

typically be inserted into a quiet sector with French or British units. This

process would expose the platoons and companies to the realities of the front

but in a manner that was methodical, deliberate, and mitigating of the numerous

risks associated with front-line service. This initial exposure was normally a

few weeks to a month or two but not more. It was the German spring offensive in

1918 that would impose an urgency across the French and AEF high commands that

would require the first American regiments and battalions to engage in combat.

The

4th Marine Brigade was rushed outside Château-Thierry where they would

engage the Germans for the first time and without either British or French

assistance. Moreover, they would rely on the unique culture of the Marine

Corps; their cohesion and discipline. They would also rely on their pre-war

training, and follow their seasoned officers and veteran non-commissioned

officers into the crucible of combat and overcome the german infantry; a very seasoned and

determined foe.

The

Battle of Belleau Wood has been studied and reassessed over the years with a

particular emphasis on the details of the fight, the chronological order of the

events as they unfolded in space in time, and on the decisions of the key

leaders within the 2nd Infantry Division, the 4th Marine Brigade, and

the 5th and 6th Marine Regiments. The historiography is constantly

refreshed owing to the myths and lore associated and recycled by each

generation of U.S. Marine. Contemporary historiography has scrutinized the

attack through the wheat fields, the hastily prepared set of orders pushed down

from Brigade to the 5th and 6th Marine Regiments, and the difficulty

with logistics resupply, often a neglected aspect of the planning in the first

actions of the AEF in World War 1.

II: The Culture of the Corps

The

U.S. Marine Corps was ‘born’ on 10 November, 1775, within the halls of a

drinking establishment in Philadelphia. “Tun Tavern” was a brewery and a bar; a

meeting place in the 1770s that is traditionally regarded as the first

recruiting station of the United States Marine Corps. As a part of the ‘Naval

service,’ Marines are soldiers of the sea; comfortable on land and shipboard. A

unique service, the Marine Corps is historically, small in numbers. Pre-World

War 1 strength was never greater than 13,000 Marines. As a ‘landing party,’ Marines

were organized to carry out raids, small sharp, short actions and more often,

they found themselves acting as a constabulary or protecting embassies and

consulates.

The Marine Corp, however, had earned a reputation within the armed forces owing

to their near constant use in overseas expeditions. Most Marines served

overseas or aboard Naval vessels. They operated with a degree of independence

and junior officers exercised authority and responsibility beyond their

stateside peers. The Non-Commissioned Officers (NCOs) or sergeants, ran the

day-to-day routine of enlisted Marines. Owing to their long service and years

overseas, the NCOs were grizzled veterans who enforced standards and

discipline. From the Revolutionary war to the Philippines, Mexico, Cuba, and

China, the Marine NCOs in 1917 influenced the culture of the rapidly expanding

Marine Corps. The fruits of their labor would be demonstrated in 1918 France.

Many young American men had to decide whether to enlist in the U.S. Army or the

United States Marine Corps. Marine Corps recruiters often highlighted the

‘overseas duty’ coupled with adventure and “splendid opportunities.”[3] The

Corps sought out unique candidates such as Private T.S. Allen. Originally from

South Dakota, and certainly not immune to the hard physical life out west in

the early 1900s, Allen remembers that “soldiers looked like husky chaps, but

there was something about the Marines you could not forget.”[4] He

recalled the Marines he first saw as alert, clean, and minding their own

business who left a deep impression. He suspected the Marines could take care

of themselves. He enlisted, trained at Parris Island and then Quantico Virginia

with the 96th Company, 2nd Battalion, Sixth Marines. He later fought and

was wounded at Belleau Wood.

Perhaps

no better example of the unique U.S. Marine Corps culture exists than the recruiting requirements imposed in 1918. The War Department

imposed a nationwide draft as part of the mobilization and a tentative plan was

submitted via the Navy Department and approved on behalf of the Marine Corps.

While “men were supplied from the selective draft,” the Marine

Corps was granted the authority to accept or reject the inductee’s if they

failed to measure up.[5] Once

the potential recruit was accepted, depending on where they lived (U.S. West

Coast or U.S. East Coast) they reported to Mare Island in San Francisco or

Parris Island, South Carolina.

The shaping and training

of recruits for service in France began, for most recruits, at Parris Island,

South Carolina. The Recruit Depot at Parris Island, formerly known as Port

Royal, S.C., ramped up upon general mobilization and trained over 13,000

Marines during 1918. Recruits received their introduction to the Marine Corps

and an eight-week basic training course to prepare them for the war in France. The

training included the usual physical fitness, close order drill and marching,

swimming, bayonet fighting, and obstacle courses.[6] The

most important aspect of the training syllabus was the three weeks spent on the

rifle range. The Marine Corps particularly paid attention to advanced

marksmanship which would pay dividends in France.

A

U.S. Marine veteran of northern France and Belleau Wood, Elton Mackin, provides

some interesting insight on training at Parris Island. “Americans say

among themselves - feel among themselves - there’s two things the American man

can do, he can shoot straight and play poker, and some play a pretty good game

of poker and most all of them can shoot.”[7]

The

Marine Corps during the pre-war period (1898-1917) obsessed over ‘close order

drill,’ the manual of arms, and strict control of subordinate formations. The

doctrine of the era inculcated the junior Marines with unquestioning obedience

and exacting discipline.[8] The

idea espoused in the pre-war era concentrated on gaining ‘fire superiority

which allows for maneuver, closing with the enemy, and engaging with bayonet.’

As such, discipline and adherence to superior officer’s orders and commands was

necessary in order to maintain effective control of subordinates.

Marine Corps regulations up to 1917 prohibited owning civilian attire and

disallowed the carry of knives aboard Naval vessels. Uniform care, wear, and

their appearance was given specific attention. Everything about the pre-war

Marine was a deliberate manipulation of standards, conduct, and training to

reinforce obedience and strict discipline.

Obedience to orders was a necessity when a Rifle Company of 250 men, for

example, was formed up. Four rows of men, spaced out 5 yards between men,

typically advanced at a set pace in order to close with a final advance by

bayonet. While this was the preferred manner of employment in the Philippines,

or Cuba and the Dominican Republic, it would not hold whatsoever in the modern

battlefields of France in 1918. Belleau Wood, as shall be seen, would change

the doctrine, close order drill, and centralized control of formations.

III:

Pre-World War 1 Period: 1898-1917

The

history of the Marine Corps, prior to 1914, was a history of small expeditions,

remote duty and limited combat for Marine detachments. On April 1st, 1917, the

entire U.S. Marine Corps end strength was 13,725 personnel. By late 1918, the

Marine Corps grew to over 75,000 men. Before World War I, the Marine Corps,

like the Army, “organized itself into regiments but, unlike the Army, the Corps

did not have a fixed structure below the regiment level.”[9]

The

nature of the Naval service required the use of small Marine detachments that

served on capital ships (typically battleships and gun cruisers), that provided

security, enforced discipline, and on occasion, served as small landing

parties. Additionally, U.S. Marine detachments served as ‘constabulary’ forces

in order to protect U.S. legations, embassies, or in anti-guerilla operations

while representing U.S. interests abroad. Such was the case of the U.S. Marine

Corps between 1898 and 1917.

With

Europe engaged in war between 1914 through 1917, the U.S. Army and the U.S.

Marine Corps busied themselves studying and preparing. Although they did not

possess the combined arms experience of the French or British armies, the

active officers and NCOs were seasoned and professional. In the case of

the U.S. Marine Corps regiments, they arrived in Europe with a solid corps of

veteran Non-Commissioned Officers, who on average, had years of experience. The

most senior NCOs in the Rifle Companies and Battalion staffs had served in the

Spanish-American War (1898) or in the Boxer Rebellion in China (1898-1901).

The U.S. Marine Corps contributed over 2,055 Marines to the Spanish-American War with 600+ conducting a landing and engaging in ground combat in Cuba.[10] Marines landed in Cavite, Philippines with Admiral Dewey’s squadron and would land unopposed in the capture of Guam. While none of these actions can compare to a three-day period in northern France, these actions often required preparations, tactical and logistics planning, and key actions of NCOs such as rehearsal, inspections, task organization for critical tasks and the like.

The

Marine Corps spent the post-Spanish American war period (early 1900s),

reinforcing or supporting American foreign policy interests across the Pacific

and the Caribbean. After the end of the Spanish-American War in 1898, the

U.S. Army and one Battalion of U.S. Marines established themselves in the

Philippines. Over the course of 24 months, the U.S. Army engaged guerillas

across Luzon, Philippines and the U.S. Marine Corps established the 1st Marine

Regiment in Cavite. While the Marines protected the Naval port of Subic Bay,

they routinely supported the Army against guerillas. The 1st Marine

Regiment, additionally, deployed Marines to legations and American interests in

Korea, Peking (Beijing), and Shanghai. The Marine Corps in the Pacific

maintained a foot print in some capacity right through the Second World War.

The

Caribbean also saw tremendous employment and small unit action by Marine Rifle

Companies and small battalions. In 1910 U.S. Marine Corps Major Smedley

D. Butler arrived off the coast of Nicaragua. He commanded over 250 Marines and

they would assist in implementing security and protecting American interests in

Bluefields. By 1912, the Marines would occupy Nicaragua and operate there until

as late as 1933. Nicaragua, along with Haiti, Cuba, and the Dominican Republic

all shared issues with political instability that affected U.S. government and

economic interests.

In

1912, 750 Marines were landed in the Dominican Republic.[11] The

Marines departed in 1912 only to return in 1916. The Marines would operate as

an anti-guerilla and constabulary forces in the Dominican Republic until 1924.

By 1915, 330 U.S. Marines landed in Haiti for occupation duty. Over a five-year

period, the Marines would engage in anti-guerilla operations, establish base

camps, train the Haitian Gendarmerie and fight two different uprisings (the 1st and

2nd Caco Wars).

The

Spanish-American war through 1917 saw the United States Marine Corps engaged

across the Pacific and the Caribbean effectively supporting and enforcing U.S.

foreign policy interests. The benefit of these ‘expeditionary’ deployments

played out in the professionalization of its NCO corps and officer corps.

Leadership was developed and routinely practiced as each of the expeditions

mandated independence, self-reliance, critical planning skills, and small unit

tactics. While all these experiences were eclipsed by the savagery of the

industrial-scale fighting in World War 1, lessons were learned that carried the

Marines through the tough fighting across northern France.

IV: Training and Mobilization for War: 1917

Against

General Pershing’s initial desire, the 2nd Infantry Division stood up in

October 1917 as part of the American Expeditionary Force (AEF). The

Division was comprised of with one U.S. Army Brigade and a U.S. Marine

Brigade. Both Brigade’s consisted of two Infantry Regiments and one Machine Gun

Battalion. The Marine Corps provided the 5th and 6th Marine Regiments

along with a machine gun battalion to form up the 4th Marine Brigade.

The whole of the 2nd Infantry Division was created, ad hoc, and included

active U.S. Army Infantry Battalions assembled from battalions stationed along

the U.S.-Mexican Border. The Army battalions were transported to Syracuse, New

York, and then on to France in 1918. 2nd Division staff understood

the necessity for preparations and training and maximized all available time

towards that end.[12] The

official 2nd Division History remarks that “a program of intensive

training was projected, but it was not to go forward” as logistics and

competition for resources inhibited fully formed training programs. The

history continues further, stating that “there were too many things to be

done by the Americans in- France, and too few Americans -- yet -- to get them

done.”[13]

The

2nd Division was assembled from active personnel, including its officers

and non-commissioned officers. The official history remarks that at no time did

the Marine Brigade, for example, during its time in combat and attached to the

2nd Division, did the Brigade ever receive ‘draftees,’[14] The

4th Marine Brigade, then, deployed with Marine veterans of pre-war

service. However, much like the 2nd Division, the 5th Marine

Regiment, was also hastily assembled from various detachments across the Marine

Corps. From ships detachments, stations, and small outposts, the regiment was

assembled and immediately shipped off to France. Additionally, the 6th Marine

Regiment, also scratch built for wartime service, was assembled at the new

Marine Corps base in Quantico, Virginia in July 1917.

Both,

the 5th and 6th Marines were manned, equipped and hurriedly deployed

for duty in France. The 5th Marines stood up in mid-June of 1917 and

arrived in France on 27 June, 1917. They were immediately put to work in

the ports performing manual labor stevedore, and guard duty. The 6th Marines

trained from July until October, when the first elements joined up with the 5th Marine

Regiment in France.[15] The

Commandant of the Marine Corps purposely selected the best officers from across

the Corps to man the new 4th Marine Brigade. To a man, every Company,

Battalion, and Regimental commander was a seasoned veteran and “ many of its

leaders had extensive experience with the Corps around the world before World

War I.”[16]

The U.S. Army Brigade and the 4th Marine Brigade were comprised of active

personnel, the officers and non-commissioned officers (NCOs) were typically long-service

veterans who arrived with what experiences and training they had prior to 1918.

In the case of the Army regiments, both had

served along the Mexican border conducting patrolling and area security

operations. For the Marines, the officers and particularly the NCOs, they

brought with them their collective experiences in expeditionary and

anti-guerilla operations from the Philippines, Cuba, Nicaragua, the Dominican

Republic, and Haiti. The pre-war period, between the Spanish-American War of 1898

and 1917, saw rapid developments in firearms technology including widespread

use of the machine gun (firing automatic links or belts of ammunition) and

rifled artillery, which extended its effective range and accuracy.

Infantry formations, nevertheless, relied on the bolt action rifle: the

Springfield 1903 coupled with a bayonet.

At the turn of the century Marine Corps manpower hovered around 13,000 or so

personnel. This included officers, NCOs, and junior enlisted rank and file,

spread out in small detachments, legations, and naval vessels. As a small

organization, the Marine Corps adopted or simply copied many of the U.S. Army

regulations and doctrine. An example is found within “The Landing Force

and Small Arms Instructions: United States Navy 1916.” Interestingly, this

manual was first published in 1905 with a recommendation “to follow the Army in

all fighting formations.”[17]

Further evidence of the Marine Corps use of Army regulations and guidance can

be found in the U.S. Army instructions disseminated across the AEF in 1918.

“Instructions for the Offensive Combat of Small Units,” published in May 1918,

was signed off by General Pershing and oriented towards the conditions the AEF

would face in France. It is a sobering manual as it includes elements of

intelligence gathered between 1914 and 1917 and conveys the difficult

challenges that AEF would come face-to-face with once in France.

Historically speaking, this manual has much in common with the basic principles

of any combined arms formations and the tactics to be employed. Assault,

support by fire, ‘rushes’ by smaller groups with covering fire, artillery

employment at the point of attack, envelopment, flanking, synchronization and

coordination of both, supporting fires and adjacent friendly units with an

emphasis on flexibility and mobility.[18]

Neither regiment, once in France, was afforded much opportunity to train beyond

marksmanship, drill, machine gun ranges, bayonet drills and classes in the

French model chemical protective mask use. Most of the training concentrated on

life in the trenches.[19] Training introduced the Marines to

life in the trenches, building dug outs, manning observation posts and reacting

to simulated gas and artillery attacks. Physical training included ‘hardening’

or conditioning, through forced marches; hiking with full kit, and in all types

of weather.[20] The soldiers and Marines of the

newly formed Second Infantry Division, after a period of two to three months,

were introduced to the front-lines. They were purposely employed in quiet

sectors with accompanying French or British formations to slowly and

deliberately acclimate the troops to the conditions of the Western Front.

A

unique aspect of the American culture, it seems, played out in the trenches,

fields, and forests of northern France once the U.S. Army and especially, the

U.S. Marine Corps arrived in 1918. The deliberate, well-aimed, and precise

employment of the rifle was remarked upon by both German and American veterans

of the Battle of Belleau Wood. The Marine Corps prioritized rifle marksmanship

well before World War 1 service. Marksmanship coupled with a healthy dose

of bayonet training was the main aspect of training for the Marines in the

Rifle Companies.[21] Close combat, hand-to-hand, with

bayonet, knife, and shovel, the Marines were ruthlessly drilled to parry German

bayonet attacks and to counter with deliberate strikes.

The subordinate Battalions within the 4th Marine Brigade used every available moment to train. The 3rd Battalion, 6th Marines, for example, arrived in France on 12 November 1917. The battalion was immediately put to work across the ports, docks, and warehouses. Two months later, on 12 January 1918, the battalion joined the rest of the 4th Marine Brigade in the Second Division training area at Carbon Blanc. The battalion’s official history remarked that “the training was very severe due both to the strenuous schedule and the winter.” [22]

The Marines in the 4th Marine Brigade received training in Quantico,

Virginia prior to shipping off to France. For the newest Marines, inducted in

1917, they had all received the requisite 8-week basic training program at

Parris Island, S.C. or Mare Island, San Francisco. A further month or two at

Quantico provided an opportunity to develop cohesion and make basic

preparations for combat in France. As has been noted, the 5th and 6th Marine

regiments were ad hoc organization’s purpose built for operations in France.

While the 5th Marines was working as stevedores in the ports, the 6th Marines

was still being organized.[23] Once the orders were approved for

the stand-up of the Second Divisions, all the battalions and support companies

were assembled in Carbon Blanc. On balance, the Rifle Companies and the

platoons had the minimum of training in modern combined arms operations. The

seasoned officers and veteran NCOs would carry the battalions through the first

actions. From thereafter, it would be the junior Marines who’d carry the

battalion al, the way to November 1918.

V:

The Leadership

A survey of the prototypical NCO in the Marine Corps in October 1918 had ten or

more years of service. Many had served most of their careers overseas in the

Philippines, the Dominican Republic, or aboard a U.S. Navy gun-cruiser. Marine

Sergeant Kocak and First Sergeant Daly are synonymous with the veteran NCO

corps across the 4th Marine Brigade. Sergeant Kocak, an immigrant from

Slovakia, was ‘an old hand’ to his new charges in the 5th Marines. Kocak

was serving in the Dominican Republic when he was ordered to Quantico to fill

out the new 5th Marine Regiment.[24] Kocak

led from the front and aggressively engaged the German infantry on numerous

occasions in close combat employing bayonet and grenades. Kocak was

killed in action in Blanc Mont Ridge in July 1918. For his actions he was

awarded the Medal of Honor.

First Sergeant Daniel Daly found a home in the Marine Corps and served in

China, Haiti, and aboard numerous U.S. Navy vessels. He served in the Marine

Corps from 1899 until 1929 and retired as a Sergeant Major. For his action in

China during the Boxer Rebellion, he was awarded the Medal of Honor. While in Haiti,

his small patrol was ambushed by hundreds of Cacos guerillas. Daly was awarded

his second Medal of Honor for actions then. As a First Sergeant of the 73rd

Machine Gun Company, Sixth Marines, he was awarded the Distinguished Service

Cross for action in Belleau Wood.[25]

The officers and especially, the Company and Battalion Commanders, were

seasoned veterans who had also served most of their careers overseas. Captain

Llyod W. Williams, ‘skipper’ of the 51st Company, 2nd Battalion, 5th Marines

was commissioned in 1910 and by 1918, had served a year if sea duty on the USS

Mississippi, in Panama, Nicaragua, Guam, and Cuba. He was highly rated by his

superiors and led his men from the front. He was killed in action on 12 June

during the Battle of Belleau Wood. The Marine commissioned many of the its

junior officers from the ranks. 2nd Lieutenant Kipness, another immigrant

(from Russia) enlisted in the Marine Corps in 1904. Kipness, as an enlisted

Marine, served in Panama, Haiti, Mexico and deployed to France as a First

Sergeant before commissioning.

The 6th Marines Regimental Commander, Colonel Albertus Catlin, wrote of

Major Berton Sibley, his subordinate commander of 3rd Battalion, 6th Marines,

that he was a ‘picturesque character’ who was ‘thorough in all that he did’ and

that ‘his boys followed him and loved him like warriors of old.’[26] Major

Sibley led from the front and took over one of his subordinate Rifle Companies,

leading it in Belleau Wood when all the company officers were wounded. Sibley

was awarded the Navy Cross for his actions at Belleau Wood.

The Regimental skipper, Colonel Catlin, was an old hand as well. A U.S. Naval

Academy graduate, Colonel Catlin led his regiment (the 6th Marines) at

Belleau Wood and shared in the stress and hardship of the hard-fought

engagement. Colonel Catlin, a veteran of the Spanish-American War, was the

Marine Detachment Commander aboard the USS Maine when it exploded off Cuba.

Colonel Catlin fought in Vera Cruz, Mexico where he was awarded the Medal of

Honor.[27]

The NCOs and officers that led the 4th Marine Brigade at Belleau Wood were

seasoned veterans of expeditionary warfare. As professionals, they understood

that their tasks would require tremendous effort and decisive leadership as

they would be challenged in the most arduous conditions they had ever

experienced. Nevertheless, their seasoning and real-world experiences molded

them, as leaders, to set the example, lead from the front, share in the

hardship of their subordinates, and mostly, to make sound and steady decisions

when in action.

VI: The Battle of Belleau Wood

There

is a slight, almost gentle rise, from the wheat field to the woods. Even with

the wheat high, there is little wonder as to how and why the Marines

experienced the mass of casualties as they worked their way towards the wood.

The landscape feels open with clumps of forest and wood that breaks the

sightlines. It was inside each of these clumps of forest and wood that the

Germans were well dug in with machine guns set for interlocking fields of fire.

The open wheat fields towards the German’s front were ranged for artillery and

the Germans were in fortified and protected defensive positions. A herculean

effort of unanticipated sacrifice would be necessary to dislodge the Germans.

What

transpired over the course of three weeks is bound up between fact and fiction;

the facts, however, are undisputable. The U.S. Marines attacked on June 6th,

1918, suffered tremendous casualties and finally took all of Belleau Wood by 26

June. The U.S. Marine Corps that entered Belleau Wood, had little in common

with the U.S. Marine Corps that exited those woods in late June. The

historiography of the battle includes stinging criticism of the doctrine and

tactics employed on 6 June. Large multi-row formations of Marines neatly spaced

and moving forwards in unison commenced the attack. No smoke was used to

obscure their advance. A 30-minute artillery barrage was employed to cover and

support their attack, rather than a coordinated direct support effort intended

to reduce the German defenses. The Marines formed in the blackness of night for

a 03:45am attack. Several companies failed to link up on time. The attack went

in the early morning with a rising sun. The attack advanced and the Marines

clawed and scraped their way into the edge of the woods. They did so at a

tremendous cost.

From

personal accounts and memoirs, the Battle of Belleau Wood was every bit as

savage as portrayed. The Germans pushed hard and launched at least six separate

attacks over the weeks of close fighting. Elton E. Mackin, a private who served

in 1st Battalion, 5th Marines relays an interesting and significant

aspect of the fighting. “We took Belleau Wood over a period of weeks, a bit at

a time.”[28] Mackin

goes on to further explain that the Marines ‘attacked the Germans at all hours

of the day,’ opting to adopt an unpredictable method rather than the standard

‘dawn attacks’ of the British and French. Lastly, he comments that ““European troops,

in this case, Germans and Austrians for the first time in history ran into

aimed rifle fire which begins to kill at 800 yards.”[29]

Mackin further commented that “we were taught, we were trained to gauge with the scavenge on the bayonets.” News reports across Europe and the United States reported “hand-to-hand fighting occurred during the night”[30] as the Marines captured over 250 Germans between the 6th and 9th of June. The fight would ebb and flow as the Marines would attack, settle in, defend a German counterattack, and then attack again. On the 12th. The Marines secured a breakthrough in the fighting that broke the back of the German defenses. The fighting in Belleau Wood was not the trench-warfare that dominated the preceding years. It was open warfare and “was very much a maneuver warfare battle” as “the Marines hit a gap and poured through it.”[31]

The Marines learned quickly to implement

‘covered rushes’ whereby one element of 5-6 Marines would move 10-20 meters

under the cover of another 5–6-man elements. They would bound this way into the

woods constantly seeking cover. When covering, they would lay down a

suppressive fire in order to keep German heads down. It was a slog as evidenced

by the three constant weeks of shelling, machine gunning, and bayonet fighting.

More so, the evidence in Marine casualties; almost every Rifle Company

commander was wounded or killed, numerous NCOs and old Corps veterans were also

either killed or wounded. Junior Marines became veterans in those three weeks.

Their steep learning curve, however, was overcome by their esprit; their dash

and as the French so often pointed out, their élan.

A critique of the Marine attack for

Belleau Wood would highlight the failure to conduct thorough reconnaissance,

the poor synchronization of supporting arms, poor coordination of mutual

support, poor communications, failure to prepare reserves, the lack of

contingency plans, and the failure to properly plan follow-on logistics support

to the main element conducting the attack. Despite these glaring shortcomings,

of which all contributed to the lengthy roster of casualties, the 4th Marine

Brigade ‘had used up four German Divisions’ in the Battle of Belleau Wood.[32]

The

wheat field was a murder-trap that quickly consumed platoon after platoon. A

platoon of 48 men was quickly reduced to 4 uninjured men as the German machine

gunners focused on the open field.[33] Somehow,

the Marines kept pressing forward. In small groups fighting independent

actions, but sharing in the same objective; taking out every single German

machine gun or hasty trench.

Figure 1: Map of Bois de Belleau. The Marine “limits of advance” are denoted in

black, red, green, and

blue ‘China marker.’[34]

VII: Conclusion

Statistically speaking, the 4th Marine Brigade should have ceased to

effectively function on 26 June 1918. The first three days of combat in Belleau

Wood the Brigade suffered over 1,447 casualties and in the following six days

saw another 1,714 casualties. [35] The

effect of casualties on any fighting formation is debilitating but the numbers

at Belleau Wood are significant. The combat quickly devolved into sharp small

fights between squads and sections. Communications was terrible as senior

commanders never quite had a common operating picture of the battlefield. The

battle was ultimately left to the Company and Platoon Commanders along with

their NCOs. Some battalions lost many of their officers in the first three days

of action as the Marines ground their way deeper into the wood. The NCOs and

younger Marines would lead the way as “1st Battalion, 5th Regiment, lost

roughly 90 percent of its commissioned ranks as it fought across open ground to

take Hill 142.”[36] Over

3,000 casualties in the first 20 days of June, 1918 demonstrates the vicious

nature of Belleau Wood. The Brigade entered Belleau Wood with 8,118

Marines on 6 June, 1918. On 30 June, the Brigade’s strength was 6,473 Marines.

The 4th Marine Brigade was a scratch built ad hoc formation purposely

organized for duty with the U.S. Army’s 2nd Infantry Division. As

evidenced by the Marines’ duty as laborers and stevedores, neither regiment

spent any training period that tested the Brigade, Regiments, or

Battalion Staffs. Individual Marines, while benefiting from the Quantico

train-up period and the hours dedicated to trench clearing and bayonet drills

at Carbon Blanc (2nd Division’s training camp) never quite received an

all-arms cohesive training period that included Battalion sized live fire

training. Ultimately, the Brigade went into Belleau Wood with what it had,

seasoned and able leaders and young Marines with some grit. They certainly

needed both once they met the enemy.

The doctrine the Marines brought with them most certainly did not withstand the

realities of the sort of modern industrialized warfare they experienced in

Belleau Wood and the subsequent operations between July through November 1918.

The U.S. Army’s Provisional Infantry Training Manual (1918) sought to

address the shortcomings of Navy-Marine manual; The Landing Force

and Small Arms Instructions (1916). Massed prolonged

artillery coupled with numerous automatic machine guns and chemicals changed

the face of warfare. Nevertheless, as the doctrine changed owing to technology,

a constant reinforced itself within the culture of the Marine Corps; decisive

and aggressive leadership was first and foremost a tangible necessity which,

across the 4th Marine Brigade, was in abundance in June 1918.

The Marines at Belleau Wood, the old veterans like First Sergeant Daly or CPT Williams and Colonel Catlin from the Philippines, China, Haiti, and Cuba, led the youngsters from Parris Island and Mare Island. The Germans took a toll on the Brigade and the Corps lost a number of its old hands. But the ethos, the esprit, and the unique culture of the Corps helped transform the young Marines into leaders who continued the fight. Many new Marines filled the vacant leadership positions and they had the example of the old veterans to help them through. The pre-war focus on rifle marksmanship and bayonet close combat was effectively applied against German counter-attacks. Old doctrine, full of rows, skirmish lines, and assault lines gave way to covered rushes of smaller numbers. The veteran Marine Company and Battalion Commanders adjusted to the conditions they faced but, in the end, it was four or five Marines like Privates T.S. Allen and Elton Mackin, led by an aggressive NCO such as Sergeant Kucak, that took out the German machine guns one at a time.

It is fitting that over each grave of each U.S. Marine buried during that savage month of June 1918, a wreath of palms was laid inscribed with the words: “Hommage de Paris aux Défenseurs de la patrie” (Paris Honors the Defenders of the nation.) Brigadier General Catlin, in his post-war memoirs stated that of the U.S. Marines and the Battle of Belleau Wood, “they left in that wood some of the best blood of America”[37] and an enduring legacy.

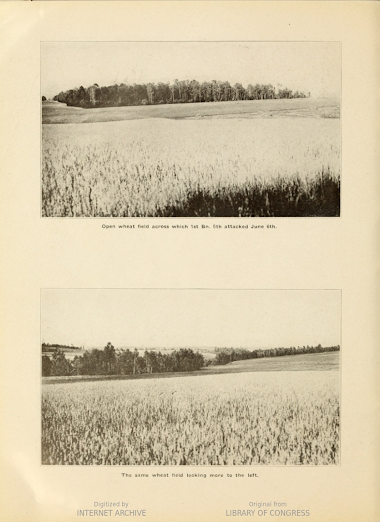

Figure 2: Photograph. The wheat fields with Belleau Wood just in front.[38]

-PRE-

CITATIONS

[1] For details on the

American Expeditionary Force (AEF) see the U.S. Center for Military

History, United States Army In The World War 1917-1919,

General Orders, GHQ, AEF, Volume 16, 1988, for background: https://history.army.mil/html/bookshelves/resmat/wwi/prologue/default/index.html

.

[2] Ralph

Stoney Bates, Sr, Maj., USMC, “Belleau Wood: A Brigade's Human Dynamics,”

Marine Corps Gazette; Nov 2015; 12.

[3] U.S.

M.C. Recruiting Card, The World War One National Museum and Memorial,

Card, Recruiting U.S. Marine Corps. One side lists words to the Star Spangled

Banner, other side gives facts on the U.S. Marine Corps. Distributed by

U.S.M.C. Recruiting Station, Peoria, Illinois.

[4] Craig

Hamilton and Louse Corbin, Ed., Echoes From Over There: By the Men of the

Army and the Marines Who Fought in France, (New York: The Soldier’s

Publishing Company, 1919), 11.

[5] Edwin

North McClellan, The United States Marine Corps in the World War,

Washington D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1920.

[6] Elmore

A. Champie, A Brief History Of The Marine Corps Recruit Depot Parris

Island, South Carolina 1891-1962, Marine Corps Historical Reference Series, No.

8, (Washington D.C.: Historical Branch G-3 Division, Headquarters, U.S. Marine

Corps, 1962) 4.

[7] Elton Mackin, Interviewed by Carl D.

Klopfenstein, Professor of History at Heidelberg College, Ohio, June 29, 1973,

Rutherford B. Hayes Presidential Library & Museums, Library of Congress Veterans

History Project, Published by Presidio Press, 1993.

[8] For

details related to U.S. Marine close order drill and employment of small units

in action , see Simmons, Through the Wheat, 16-17,34; and Millett, Semper

Fidelis, 298; further discussion includes Edwin N. McClellan, “Operations of

the Fourth Brigade of Marines in the Aisne Defensive,” Marine Corps Gazette,

June 1920, and Edwin N. McClellan, “The Fourth Brigade of Marines in the

Training Areas and the Operations in the Verdun Sector,” Marine Corps Gazette,

March 1920.

[9] Peter

T. Underwood, Col. USMC (Ret), “General Pershing and the U.S. Marines,” Marine

Corps History, Volume 5, Number 2, Winter 2019, pp. 5-20.

[10] Bernard

Nalty, The United States Marines In The War With Spain, U.S. Marine Corps

Historical Pamphlet, (Washington D.C.: Historical Branch G-3 Division,

Headquarters Marine Corps, 1959, Revised 1967), 16.

[11] Stephen

M. Fuller, CPT, USMCR and Graham Cosmas, Marines in the Dominican

Republic, 1916-1924, (Washington D.C.: History and Museums Division,

Headquarters Marine Corps, 1975).

[12] For

World War 1 pre-war training see The National Archives and Records

Administration: World War 1 Centennial, “Training the Soldier,”

https://www.archives.gov/topics/wwi/training.

[13] “The

Official History of the 2nd Infantry Division during World War 1, 1918,”

(The Combined Arms Research Library, Ft. Leavenworth, KS, 1918), 25.

[14] Ibid,

8.

[15] Anderson,

Col. William T. USMCR(Ret), The Bravest Deeds of Men: A Field Guide for

the Battle of Belleau Wood, (Quantico, Virginia: History Division, United

States Marine Corps, 2018), 2-5.

[16] Bettez,

David J., Heroic Deeds, Heroic Men : the U.S. Marine Corps and the Final Phase

of the Meuse-Argonne Offensive, 1-11 November 1918. Quantico, VA: History

Division, MCU Press, 2020.

[17] Department

of the Navy, The Landing Force and Small Arms Instructions: United States

Navy, 1916, Revised 1916, Containing Firing Regulations, 1917, (Annapolis: U.S.

Naval Institute, 1917), 5.

[18] The Command and General Staff

College: Provisional Infantry Training Manual 1918, Training Circular No.

8, War Department, Document No. 844, Office of the Adjutant General,

(Washington D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1918), 10.

[19] The National Archives, Washington

D.C., “Second Division Training In Third (Bourmont) Training Area And With

French Second Army, July 1917-March 17, 1918,” documents and (3) Film Reels,

Reel 1, Silent.

[20] James McBrayer Sellers, Lt Col,

USMC, World War I Memoirs, William W. Sellers and George B. Clark, ed,

(Pike, N.H.: The Brass Hat, 1997), 52.

[21] The National Archives, Washington

D.C., “Second Division Training In Third (Bourmont) Training Area And With

French Second Army, July 1917-March 17, 1918,” documents and (3) Film Reels,

Reel 2, Silent.

[22] Herbert H. Akers, History of

the Third Battalion Sixth Regiment, U.S. Marines, (Hillsdale, MI: Akers, Mac

Ritchie, Hurlbut, 1919), 8.

[23] George B.Clark, Devil Dogs :

Fighting Marines of World War I, (Novato, CA: Presidio Press, 1999).

[24] J.

Michael Miller, The 4th Marine Brigade at Belleau Wood and Soissons:

History and Battlefield Guide, (Lawrence, KS: University of Kansas Press,

2020), 221.

[25] Ibid,

121.

[26] Albertus

W. Catlin, With The Help of God and A Few Marines: The Battles of Chateau

Thierry and Belleau Wood, (New York: Doubleday and Sons, 1919, reprint 2016)

82.

[27] United

States Navy: Naval History and Heritage Command, “Brigadier General, USMC,

(1868-1933),”

https://www.history.navy.mil/our-collections/photography/us-people/c/catlin-albertus-w.html.

[28] Elton

E. Mackin, Suddenly We Didn’t Want to Die: Memoirs of a WW1 Marine,

(Novato, CA: Presidion Press, 1993), 50.

[29] Ibid,

4.

[30]"Steam

Roller Busy Against The Huns: Belleau Wood A Happy Hunting Ground For The

Americans Take 250 More Prisoners German Commanders Told Their Troops That Army

Had Landed In America--U. S. Artillery Brilliantly Carries Out Its Part."

The Sun (1837-), Jun 27, 1918. 2,

https://go.openathens.net/redirector/liberty.edu?url=https://www.proquest.com/historical-newspapers/steam-roller-busy-against-huns/docview/534768160/se-2.

[31] Bradley

J. Meyer, “The Battle of Belleau Wood,” Marine Corps Gazette; Quantico Vol.

102, Iss. 6, (Jun 2018): 26-29.

[32] S.L.A. Marshall, World War I,

(New York: Mariner Books, Houghton-Mifflin Company, 2001), 384.

[33] J.

Michael Miller, The 4th Marine Brigade at Belleau Wood and Soissons:

History and Battlefield Guide, (Lawrence, KS: University of Kansas Press,

2020), 143.

[34] The

Library of Congress, “Map of Belleau Wood,” James G. Harbord Papers,

Manuscript Division, Library of Congress (134.00.00). This map, from the papers

of General James G. Harbord, commander of the Marines at Belleau Wood, depicts

the course of the battle. https://www.loc.gov/exhibitions/world-war-i-american-experiences/about-this-exhibition/over-there/belleau-wood/bois-de-belleau/.

[35] 2nd Division

Summary of Operations in the World War, Prepared by the American Battle

Monuments Commission, (Washington D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1944), 23.

[36] Richard

S. Faulkner, "Doughboy Devil Dogs: U.S. Army Officers In The 4th Brigade

In The Great War." Marine Corps History 7, no. 1 (2021): 5-23.

muse.jhu.edu/article/805928.

[37] A.W.

Catlin, Brigadier General, USMC, and Walter A. Dyer, With the Help of God

and a Few Marines, (New York: Doubleday, Page, and Co., 1919), 7.

[38]Ray

P. Antrim, Where the Marines Fought in France, (Chicago, Ill: Park and

Antrim, 1919), 29.

Comments

Post a Comment