The Totalitarians: Hitler, Mussolini, and Stalin

The

Totalitarians: Hitler, Mussolini, and Stalin

Polish Air Force engages the new Luftwaffe

1939, Poland.

Perhaps the clearest

demonstration of where exactly the Western countries stood in 1939, with

respect to Adolf Hitler and Germany, is that after the Germans finally invaded

Poland in the dark hours of 1 September 1939, it took until 3 September for

Britain and France to declare war on Germany. The British waited while the

French delayed. A summation, then, of all that was both France and Great

Britain with Poland suffering the first blows of what would become the most

costly, horrific, and all-consuming World War the engulfed millions of lives.

The end of the Great War left the

European continent unbalanced. Of the Allies, the French believed the Germans

guilty and that war reparations were hardly enough to compensate for the

devastation France had suffered. Of the many by products of the Great War,

cranage and devastation was visited across Eastern France and the war had

hardly touched Germany proper. The British has suffered from the loss of men; a

whole generation and the financial cost had set the exchequer back for some

time. Of the United States, the Great War left an impression that tremendous

costs were associated with great power competition. The United States could

hardly stay the course with respect to involving herself in international

affairs and withdrew into isolation.

Germany experienced disillusionment,

frustration, and anger. Despite whatever mistakes Germany made economically in

the post-war years, the political and social conditions set the stage for the

rise of Adolf Hitler and the Nationalist Socialist Workers Party (NSDP). Hitler

came to power legitimately “because of support registered by German voters in

1932”[1]

and the German middle class, in the main, supported the early concepts and

ideology of Hitler and his political party.

hopeful to avoid any conflagration. The British Prime Minister in 1937 believed that conflict; another war much like the Great War should be avoided at all costs. But Chamberlains disposition and diplomacy experienced severe criticism.

The “most effective answer Chamberlain could have made to these criticisms was that ‘standing up to Hitler’, with or without the League and the Soviet Union, involved a serious risk of war.”[2]

In 1938 Germany would invest itself

in Austria. Germany would then threaten war; simply threaten conflict with

Europe and the Europeans turned their eyes as Germany rolled up the

Sudetenland. But Hitler was not complete. He would order German forces into

Memel, Lithuania in 1939 and any claim to Danzig and the ‘Polish Corridor.’

War, unwished for by the unprepared, was coming to Europe in spades.

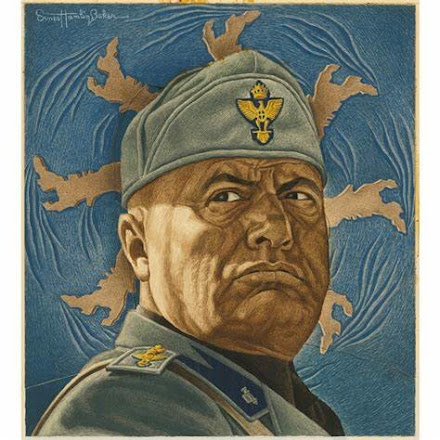

Benito Mussolini (“Il Duce”) was

ultimately welcomed by both the working class and the middle conservative class

of Italy.

Like Hitler, Mussolini was

self-taught, an ardent Socialist, and served in World War I. He spent over 8

months in the trenches as an Infantryman with the Bersagliari.

As for Joseph Stalin, he rose

through the ranks of the Bolshevik revolution on the coat tails of Vladimir

Lenin. After Lenin’s death in 1924, Stalin consolidated power and ultimately

became the supreme leader.

Prior to the start of hostilities, “Stalin hesitated for almost two weeks in May-June 1937 before giving the NKVD the go ahead for the purge of the top Red Army leadership.”[4]

When it was done, over 35,000

Officers had been dismissed with well over 4,000 murdered. Of course, after

1941, the previously dismissed were all ordered back to active duty. One such

officer ordered back to duty from imprisonment: Konstantin Rokossovsky.

[1] R.A.C. Parker, The Second World War: A

Short History, (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 1989), 2.

[4] Peter Whitewood, The Red Army and the Great Terror: Stalin's Purge of the Soviet Military, (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2015).

Comments

Post a Comment